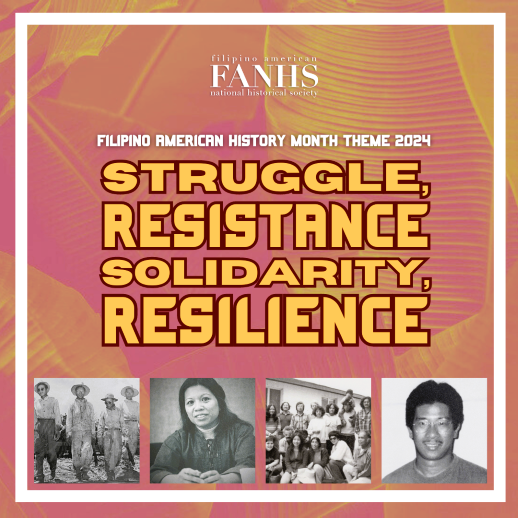

Struggle, Resistance, Solidarity, and Resilience

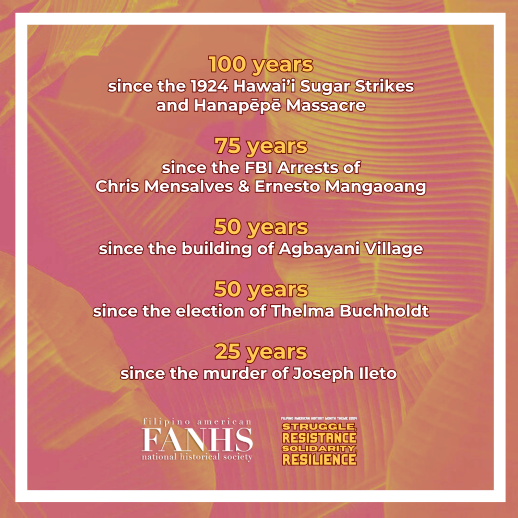

100 years since Hawai’i Sugar Strikes and Hanapēpē Massacre

75 years since FBI Arrests of Chris Mensalves & Ernesto Mangaoang

50 years since the building of Agbayani Village

50 years since election of Thelma Buchholdt

25 years since the murder of Joseph Ileto

Throughout Filipino American history, there have been instances of struggle, resistance, solidarity, and resilience. Struggle and resistance are defined as the ways that the Filipino American community has persisted through various types of systemic oppression and violence – ranging from discriminatory laws that treated Filipino Americans as second-class citizens to the hate violence Filipino Americans endured because of their race, ethnicity, and other identities. Solidarity includes the ways that Filipino Americans have organized to fight against injustice – either within their own communities or alongside other racial and ethnic groups. Resilience involves the ways in which Filipino Americans have successfully overcome adversity throughout history – despite the systemic and interpersonal obstacles they have endured.

Struggle and Resilience

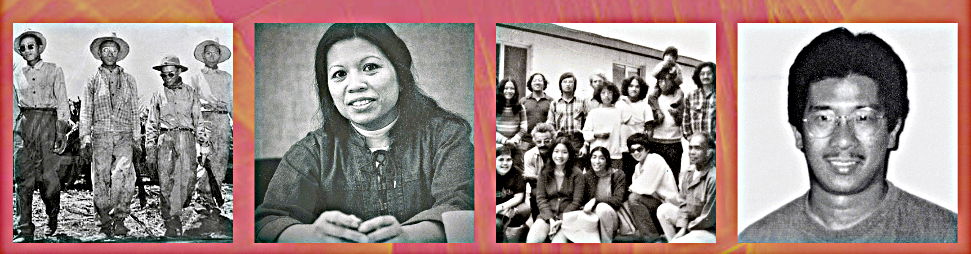

To demonstrate struggle and resilience, we recognize that 2024 marks the 100th anniversary of the 1924 Hawai`i Sugar Strike and the Hanapēpē Massacre. Prior to these events, Filipino migrants who worked on Hawaiian sugarcane plantations organized for equitable pay and other labor rights. The Filipino Labor Union (1919) was established in Honolulu by Pablo Manlapit and others – eventually leading to the Oahu Sugar Strikes of 1920, which consisted of thousands of Filipino and Japanese American sugar plantation workers striking from January to July 1920. Because the strike was unsuccessful, Manlapit organized the Filipino Higher Wage Movement and recruited Filipino workers from 23 plantations across the Hawaiian islands to strike in April 1924. The strike culminated in the Hanapēpē Massacre – a tragic event that occurred in Kauai on September 9, 1924 and resulted in the death of 16 Filipino laborers and 4 police officers. Shortly after the tragic event, Pablo Manlapit were then forced to move to the mainland because they were considered “labor agitators”.

This year also marks the 100th anniversary of the U.S. Immigration Act of 1924 – a federal law which instituted a quota system for migrants from other countries while barring migration from most Asian countries altogether. Because the Philippines was colonized by the U.S. at the time, Filipinos were considered U.S. nationals – allowing them to still migrate without quota limitations. As a result, the Filipino American population continued to grow, while other Asian American populations did not. Nonetheless, Filipino Americans who did migrate and live in the U.S. at that time still faced discrimination (e.g., being denied housing, service, or the right to own property) and violence (e.g., being targeted by hate crimes because of their race or ethnicity).

2024 also marks the 75th anniversary of the arrests of Ernesto Mangaoang and Chris Mensalvas – leaders of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), which is known to be the first Filipino-led union on the mainland United States. During the McCarthy era, activists who were outspoken against the U.S. government were charged as being associated with the Communist party. Arrested in 1949, Mangaoang and Mensalvas (who had organized the 1948 Stockton Asparagus Strike) were threatened to be sent back to the Philippines – despite being U.S. nationals (because they were born in the Philippines when it was a U.S. colony). Mangaoang fought legal battles to define his political status in order to fight the deportation orders against him- which were appealed all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. In Mangaoang v. Boyd (1953), the court ruled that Mangaoang could not be deported, eventually being identified as a “Filipino non-US Citizen-Resident,” or permanent resident. The court decisions also meant that the estimated 70,000 Filipino migrants who arrived prior to 1946 could not be deported either.

This year also marks the 25th anniversary of the 1999 murder of Joseph Ileto – a postal carrier who was killed randomly while working his shift in Los Angeles County. His murderer, Buford O. Furrow Jr., began his shooting spree at a Jewish community center in Granada Hills, CA. Upon fleeing the scene, he spotted Ileto (who he thought was “Asian or Latino”) and shot him nine times. Furrow was charged with murder on nine counts; pleaded guilty; and was sentenced to life without parole. It is the first known incident in which someone was convicted and served time for a racially-motivated murder of a Filipino American.

Solidarity

To demonstrate solidarity, we acknowledge that this year marks the 50th anniversary of the 1974 opening of Agbayani Village in Delano, California – a retirement village for Filipino American farmworkers that was established as a result of the Delano Grape Strikes (1965-1970). Five years after Larry Itliong and other Filipino laborers initiated the strike (and were later joined by Cesar Chavez and other Mexican laborers), landowners agreed to increased wages, better working conditions, and a retirement home for the elder Filipino farmworkers who had worked on the fields for decades. The strikes are considered one of the most successful labor movements in U.S. history.

We also acknowledge community organizing from other eras in Filipino American history – from the pensionados who published the Filipino Student Bulletin (1922-1937) as a way of connecting Filipino students in the U.S.; to the activists from 50 years ago who protested the Vietnam War; to the college students from 25 years ago who fought for affirmative action and Ethnic Studies. We commend Filipino Advocates for Justice for celebrating their 50th anniversary last year; as an organization based in the SF Bay Area, who have been at the forefront in advocating for low-wage workers (e.g., domestic workers, airport workers, and nurses), immigration rights, and voter registration over the last half-century. We also recognize that Filipino Americans have built coalitions with many other communities of color throughout history – from the Black-Filipino collectives created during the Civil Rights Movement to the generations of Indopino (Indigenous and Filipino) families that established a community in Bainbridge Island, Washington.

This year, we commend the many Filipino Americans throughout history who have been at the forefront of the Asian American Movement, the Women’s Movement, the LGBTQ+ Rights Movement, the Immigration Rights Movement, the Disability Rights Movement, and more. We also acknowledge the many Filipino Americans today who have fought in solidarity with other groups for racial equity and the end of state-sanctioned war and violence.

Resilience

To demonstrate resilience, we recognize that there are many Filipino Americans who have achieved success – despite the many obstacles they may have experienced due to their race, ethnicity, and other intersectional identities. For instance, 2024 is the 50th anniversary of the election of Thelma Buchholdt in Alaska, the first Filipina American woman to be elected a state legislator. In 2023, nearly 50 years later, Genevieve Mina became Alaska’s second Filipino American state legislator.

Many Filipino Americans have thrived in various other sectors – including, but not limited to, entertainment, journalism, government, business, healthcare, academia, the restaurant industry, and more. In sports, several Filipino Americans have found success, including Vicky Manalo Draves (first Filipino American to win an Olympic gold medal), Raymond Townsend (first Filipino American in the National Basketball Association), Bobby Balcena (first Filipino American in Major League Baseball), and Roman Gabriel (first Filipino American in the National Football League, who also passed in April 2024). We celebrate the Filipino Americans who competed in the most recent summer Olympics – especially Lee Kiefer who won her second gold medal for fencing. Furthermore, in recognition that we are part of a Filipino diaspora that spans the globe, we also celebrate Philippine gymnast Carlos Yulo’s 2 gold medals in vault and floor exercise (the second and third Olympic gold medals ever for the Philippines). We also recognize the Philippines’ Aira Villegas and Nesthy Petecio’s bronze medals in boxing, and the United Kingdom’s Jake Jarman (a Filipino British gymnast) for his bronze medal in floor exercise.

We also honor the many Filipino Americans who may not have made national news headlines, but who are definitely worthy of celebration. From the Filipino Americans who migrated to the U.S. to pursue their dreams, to the U.S.-born Filipino American parents who find ways to create a better world for their children, their abilities to fulfill their passions and find joy in their daily lives are commendable. Their commitment to their loved ones and their desires to represent their communities – all while fighting for social justice, being kind to others, and overcoming their everyday adversities – are all reasons for us to celebrate them. As Uncle Fred Cordova, Founding President of the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) once said: “Everybody doesn’t have to be a hero. Everybody doesn’t have to be famous. Each person who is a Filipino American is very important as a story.”

Possible activities to consider regarding our FAHM 2024 theme:

- Host workshops or panels that connect historical events like the Hanapēpē Massacre or the murder of Joseph Ileto to current issues (e.g., anti-Asian hate violence, labor rights, immigration rights, police brutality, and more).

- Conduct and share oral histories with people who lived through various time periods of Filipino American history. For example, facilitate interviews with elders who volunteered in the construction of Agbayani Village; with activists who fought for Ethnic Studies or affirmative action; or with Filipino Americans who broke barriers in their various fields.

- Read more about the Filipino Labor Union, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) and other early Filipino American labor unions, as well as the legacies of Pablo Manlapit, Ernesto Mangaoang, and Chris Mensalvas.

- Host screenings of Who We Become, Nurse Unseen, Delano Manongs, or other films that discuss the capture the theme of Struggle, Solidarity, and Resilience.

- Curate panels that highlight the various struggles, resistances, and solidarity movements that occurred in different local Filipino American communities. How has systemic oppression affected Filipino Americans in your region? How have Filipino Americans in your city or state worked with solidarity with others to advocate for justice?

Conclusion

From the painful to the triumphant – each of these moments contribute to a cumulative Filipino American history. As Auntie Dorothy Cordova, FANHS founder and Executive Director, has often said: “History is political, and it is not always pretty. There is the good, the bad, and the ugly.” FANHS believes that all of our history should be embraced and/or critically reflected upon, so that we can learn invaluable lessons and advocate for a better future.

As 2024 is also a presidential election year, we encourage our communities to reflect on the struggles that have been inflicted upon us by our government and other systems, as well as the many solidarity movements that have assisted in our community’s resistance and persistence. In doing so, we also hope to celebrate our community’s collective love and joy, which we believe – as bell hooks (author and activist) taught us – is a revolutionary act of justice.

For more information, please visit www.fanhs-national.org or visit us on instagram at @fanhs_national.

Further Readings

Alegado, Dean (2012). Blood In The Fields: The Hanapepe Massacre And The 1924 Filipino

Strike. Positively Filipino. Retrieved from: https://www.positivelyfilipino.com/magazine/2012/11/26/blood-in-the-fields-the-hanapepe-massacre-and-the-1942-filipino-strike

Chen, Jeff (2021). Remembering Alaskan Thelma Buchholdt, the nation’s first Philippine-born

woman legislator. Alaska Public Media. Retrieved from:

Dador, Denise (2024). North Valley JCC shooting: 25 years later, the enduring fight against hate

continues. ABC-7 Eyewitness News. Retrieved from:

Morrison, Noelle (2020). Ernesto Mangaoang and the Right to Be: The Fight for

Filipino-American Belonging in the United States. Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. Retrieved from https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/ernesto_mangaoang.htm

Nadal, Kevin, Tintiangco-Cubales, Allyson, & David, E. J. (2022). The Sage Encyclopedia of

Filipina/x/o American Studies. Sage. Retrieved from:

https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/123734_book_item_123734.pdf

National Park Service (2020). Agbayani Village. Retrieved from:

https://www.nps.gov/places/000/agbayani-village.htm

Viernes, Gene (1978, May). Chris Mensalvas: Daring to Dream. International Examiner.

Retrieved from: https://iexaminer.org/chris-mensalvas-daring-to-dream/